Ronald Reagan Institute

On Inconvenient Truths and Strategic Distance: Advancing American Leadership in an Era of U.S.-China Conflict

By Dale Swartz

By Dale Swartz

This is the fifth anniversary of the Reagan Institute Strategy Group. It has become something of a tradition to include an essay that chastises Washington for not doing enough to address the challenge of a rising China. In year five, I suggest we reset the frame to address the new confluence of forces facing the United States. It is no longer diagnostic to talk about the “rise of China.” Beijing under the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has arrived as a peer superpower that has both the capacity and intent to assert global dominance across all major vectors of national power.

By now, the ambition of Beijing under President Xi Jinping to remake the world is clear. He wants to disband Washington’s network of alliances and purge what he sees as “Western” values from international bodies. He wants to knock the U.S. dollar off its pedestal and release America’s hold over a range of critical technologies. In his new multipolar order, global institutions would be underpinned by Chinese notions of common security and economic development, Chinese values of state-determined political or human rights, and Chinese technology. China will no longer have to fight for leadership because it will have solidified its place at the center of a redefined international order.1

This vision runs counter to American (and Western) ideals and foreign policy priorities. The superpower competition that sits behind it is, and likely will remain, the greatest threat to the American-led international order since World War II. The world has firmly entered a perilous era of great power conflict. Regardless of your historical paradigm of choice (the Cold War, the Concert of Europe, or the Thucydides trap), reinvigorated American leadership is crucial for global stability. Conservative internationalist principles remain as important as ever. History has shown the dangers of American isolationism. When the United States turns inward, it creates a power vacuum that leads to instability, conflict, and the rise of rival powers. We are seeing this play out in real time in Ukraine and Israel. Beijing and Moscow are happily stepping into the breach.

The good news is that we have a range of levers and strategies to compete successfully and still have room to hold our own, despite being 20 years late.2 I argue that this first requires confronting four “inconvenient truths” about competition with China and changing the paradigm to the idea of strategic distance.

Four inconvenient truths that will shape competition

Rewriting the Indo-Pacific narrative starts with an honest conversation outside of Beltway policymaking circles about timeline: the Chinese “pacing challenge” is both urgent and enduring.

First, Beijing’s economic growth engine is sputtering, and we are less likely to see enduring economic growth going forward—but this does not mean Washington can “wait out” Chinese economic decline. The narrative of “peak China” is tempting in its simplicity but fails to adequately capture the economic reality shaping China’s future. Beijing will have to cope with a range of structural challenges (e.g., unfavorable demographics, high debt load, poor productivity, sclerotic state-level corporate growth in many sectors, and overreliance on an export-led industrial policy misaligned with Chinese consumption).3 Some thoughtful commentators have shown the striking parallels between China’s current situation and that of Japan before its 1990s “lost decade.”4

These trends are worth noting. Yet even if China’s GDP never surpasses that of the United States (as is now more likely the case 5), its economic influence and sheer size will ensure it retains plenty of capacity to drive its will. Moreover, China’s capacity for adaptation and innovation should not be underestimated. The country’s transition towards innovation-driven growth with a new class of high-tech national champions, coupled with its vast domestic market and expanding middle class, ensures continued economic dynamism. This focus on high-value manufacturing and technological advancement, as evidenced by its strides in artificial intelligence and renewable energy, will solidify its role as an economic powerhouse. Some decoupling has taken place—and some degree of geoeconomic diversification is desirable to drive American competitive advantage and domestic resilience—but China remains deeply integrated into the global economy through trade, investment, and infrastructure. This will underwrite its continued relevance as a leading global power.

Second, the Western preoccupation with the security of Taiwan—while critical to preserving Indo-Pacific security—is myopic. A solely Taiwan-centric approach may inadvertently embolden China to pursue aggressive actions elsewhere. While Taiwan occupies a crucial position in the Indo- Pacific, an all-encompassing focus on its defense may divert attention and resources from other pressing security challenges in the region. China’s ambitions for a sphere of influence extend far beyond Taiwan, and its strategic goals for the island have not changed meaningfully in 50 years. The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) is actively engaged in territorial disputes in the South China Sea, seeking to assert control over vital shipping lanes and resource-rich waters. Simultaneously, Beijing’s influence over North Korea’s volatile regime and its ongoing military modernization present additional threats to regional stability. Additionally, as Japan modernizes its military capabilities in response to China’s assertiveness, the potential for conflict with a historic adversary is rising.

A more comprehensive strategy is required: one that addresses the multifaceted nature of China’s military expansion across the Indo-Pacific. This necessitates allocating resources to counter China’s influence in the South China Sea, deterring North Korean provocations, and deepening engagement with Japan, India, and AUKUS in stronger partnerships on regional security.

Third, China has moved from a technological imitator to an innovator, making a tech containment strategy challenging and potentially impossible going forward. Too many in Washington comfort themselves with the narrative that China cannot truly innovate and that the United States therefore has little to worry about if exports of critical technologies are restricted. China has made remarkable gains in key battleground technologies such as space exploration, genomics, AI, and quantum computing. China is rapidly catching up to the United States in total investment and intensity in R&D, and leads by a wide margin in development of a STEM workforce, patent production, and number of scholarly articles in the basic sciences and engineering.6 While the Biden Administration has had some near-term success in banning the export of leading-edge semiconductors to prevent them from fueling the Chinese war machine, these gains are likely temporary as Beijing intensifies its investments in more advanced chips while also reducing market share for U.S. firms.7

Finally, the competition is ideological and runs much deeper than X’s personal preferences. China almost certainly will remain antagonistic to core tenets of the U.S.-led international order for the duration of Xi’s (lifelong) leadership, and perhaps irrespective of the ruling party. After Mao Zedong died, Deng Xiaoping and his colleagues sought to prevent the overconcentration of power by introducing fixed terms of office, term limits, and a mandatory retirement age; delegating authority from the Communist Party to government agencies; and holding regular meetings of Party institutions. All these moves were designed to decentralize authority, regularize political life, and check dictatorial power. The centerpiece of the institutionalization project was the practice of regular peaceful leadership succession followed by Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao. Yet today, Xi is taking China back to a personalistic dictatorship after decades of institutionalized collective leadership. Like his role model, Vladimir Putin, Xi has clearly signaled his intention to remain in office indefinitely. The global revisionist narrative is so central to Xi’s leadership and the broader CCP enterprise that it is hard to imagine a fundamental ideological shift that aligns with Washington’s goals, based on policy documents.8

Reimagining the framework for competition: restoring America’s strategic distance

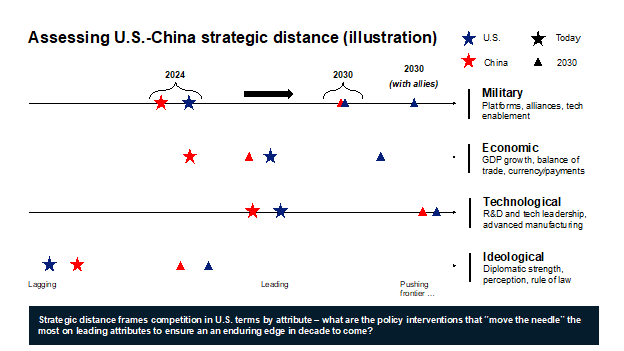

How can the United States regain the initiative to compete with China not just in the Indo-Pacific but globally? I suggest applying the concept of “strategic distance.”9 Strategic distance came into more common practice in the private sector during the pandemic-era disruptions, and starts with identifying drivers of power or competitive advantage (in this case, national-level military, economic, technological, and ideological strength), assessing a baseline for each attribute, and devising a strategy to create sufficient competitive “distance” against rivals through leap-ahead capabilities—where necessary and where resources allows. China (like Russia) has historically been deterred through strength, and strategic distance means that we are measuring against ourselves rather than some outdated notion of matching Chinese actions or capabilities.

Military (platforms, alliances, tech enablement): By all indications, U.S.- China strategic distance continues to erode on this dimension, suggesting that overmatch may be impossible and even remaining at parity could be a challenge. Potential policy implications include:

Start with a credible military deterrent across domains. A step change in military investment (platforms, interoperability, training) will be required to deter a full range of China conflict scenarios—not just one time but for a generation. In a war against China, U.S. forces could run out of critical munitions in a week.10 Filling the production and military tech gap suggests an implied “run rate” of five percent defense spending as a share of U.S. GDP.

Washington will need all its allies to maximize strategic distance. Beijing desperately wants to frame this as the United States versus China alone. America’s network of alliances in the Indo-Pacific is crucial for deterring aggression and maintaining regional stability. By strengthening these partnerships and working together to counter China’s military and economic expansion, the United States can ensure a free and open Indo-Pacific.

Economic (GDP growth, balance of trade, currency/payments): This factor may be a potential bright spot, where U.S.-China strategic distance increases (based on continued growth, productivity gains and financial leadership). Potential policy implications include:

Full economic decoupling is neither feasible nor desired, but the United States will need to bolster its economic resilience. This involves reducing reliance on China for critical supply chains, diversifying manufacturing bases, and promoting domestic production of essential goods. The goal is to mitigate vulnerabilities stemming from overdependence on China while minimizing the risk of a full-scale trade war. Strategic distance also requires strengthening domestic resilience by investing in strategic infrastructure, STEM education, and workforce development. A strong and prosperous domestic economy is essential to withstand external pressures and compete effectively on the global stage.

Double down on leadership in financial markets by countering Chinese and Russian efforts to dethrone the dollar, encouraging the development of “patriotic” public/private capital that advances U.S. industrial and innovation goals (even if at a diminished rate of return), and placing greater restrictions on “adversarial” capital (which runs counter), such as by expanding outbound investment screening.

Technological (R&D and tech leadership, advanced manufacturing): U.S.- China tech competition is likely to remain a hard-fought battleground for decades and could prove decisive as the engine behind leap-ahead advances in the other domains (e.g., economic productivity acceleration and military innovation). Potential policy implications include:

Accelerate American innovation.11 Tilt technological investments toward R&D and advanced manufacturing in critical industries, building capacity for leap-ahead capabilities in key discriminators (e.g., AI, quantum, biotech, advanced materials) and ensure that America owns the tech platform standards for the next generation. Re-tune the U.S. government’s R&D enterprise (and annual $200B+ investments) to ensure alignment with those objectives and accountability to return on investment.

Create and expand pathways for the best and brightest globally to learn, work, and thrive in the United States and become citizens. Build a talent bench in the U.S. government that is fluent across all the key levers of strategic distance (military, economic, technological, ideological) and is well-equipped to make decisions and guide investments across these areas seamlessly.

Ideological (diplomatic strength, perception, rule of law, soft power): Washington is steadily losing ground on this dimension, which could challenge the task of building global talent and alliance networks. Potential policy implications include:

Invest in American diplomacy to build deeper partnerships in the non-aligned world (particularly in the Global South) and counter Chinese malign influence.

Looking in the mirror: Key questions to grapple with as we move forward

U.S.-China competition, while enduring, does not have to be zero-sum. A focus on sustaining American strategic distance could create a unifying, positive message for the American people while investing in leap-ahead capabilities that will have multiplier effects throughout the U.S. economy. We have all the tools and the pieces of the right strategy, but we now need clear, sustained messaging and a commitment to implement the strategy over a generation or longer.

This will not be easy or happen overnight, and it will require us to grapple with some critical questions as a nation:

Can we refashion key policy tools without mimicking the Chinese approach? (e.g., thoughtful industrial policy that tips the scales without picking winners/losers or designating national champions, or government-supported R&D that preserves the animal spirits of private sector innovation)

How can we design this campaign as a 21st century national project (akin to the Space Race) that hardens political will and popular support across the political spectrum, and over the longer term?

What are the hard choices on government investment in a constrained fiscal environment?

How do we build government capacity to support these aims while preventing the continued creep of the administrative state and regulatory overreach?

How will we strengthen and support American democracy and rule of law to boost ideological leadership?

Xi Jinping, “Implementing the Guiding Principles of the Central Conference on Work Relating to Foreign Affairs and Breaking New Ground in Major-Country

Diplomacy with Chinese Characteristics,” Speech, https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/eng/wjb/wjbz/jh/202405/t20240527_11312292.html.Note: The Biden Administration advocated for a concept of “integrated deterrence,” rooted in nuclear deterrence theory but expanded to encompass

whole-of-government efforts, by managing strategic competition, building de-escalatory off-ramps, offer opportunities for cooperation, and preparing for

all possibilities. Others can opine on the efficacy of this strategy, but it has largely failed to catch on outside a small number of policy and force planners in

Washington.Zongyuan Zoe Liu, “China’s Real Economic Crisis: Why Beijing Won’t Give Up on a Failing Model,” Foreign Affairs 103, no. 5 (August 6, 2024), https://www.

foreignaffairs.com/china/chinas-real-economic-crisis-zongyuan-liu.J. Stewart Black and Allen J. Morrison, “Can China Avoid a Growth Crisis?,” Harvard Business Review, September 2019, https://hbr.org/2019/09/can-china-avoida-

growth-crisis.The Economist, “When Will China’s GDP Overtake America’s?,” June 7, 2023, Chart, , June 7, 2023, https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2023/06/07/whenwill-

chinas-gdp-overtake-americas.Ian Clay and Robert Atkinson, “Wake Up, America: China is Overtaking the United States in Innovation Capacity,” Information Technology and Innovation

Foundation (ITIF), January 23, 2023Sujai Shivakumar, Charles Wessner, and Thomas Howell, “Balancing the Ledger: Export Controls on US China Technology to China,” CSIS, February 21, 2024

Rush Doshi, “The Long Game: China’s Grand Strategy to Displace American Order,” Oxford University Press, August 2, 2021.

Note: Not to be confused with “strategic depth” – this distance is metaphorical, not geographic!

Seth Jones, “Empty Bins in a Wartime Environment: The Challenges to the U.S. Defense Industrial Base,” CSIS, January 23, 2023

Note: For more ideas on this topic, see the Reagan Institute’s 2024 National Security Innovation Base Report Card, where the author served as an Advisory

Board member and co-author.

Join Our Newsletter

Never miss an update.

Get the latest news, events, publications, and more from the Reagan Institute delivered right to your inbox.