Ronald Reagan Institute

Funding the Fight: The Paradoxical Path to Reversing Defense Decline

By Mackenzie Eaglen

By Mackenzie Eaglen

Washington knows its military is teetering on the brink of insolvency, but it seems incapable of solving hard, generational problems before the next crisis. Indeed, exactly what constitutes a crisis that makes these systemic problems worth addressing is no longer clear. In the not-too-distant past, supporting two grinding, existential wars for allies in Europe and the Middle East would have likely been enough to galvanize policymakers for change. Throw in a half year of non-stop operations in the Bab el-Mandeb Strait fighting Iranian proxies and depleting decades-worth of missile inventories in mere weeks, and the moment seems ripe for action.

Yet it is the same old in the nation’s capital. There is little urgency or sustained leadership to tackle all the challenges plaguing the Department of Defense (DoD) at once.

What steps can be taken now to start closing the gap of sagging deterrence across three theaters while preparing for the moment when Washington “breaks the glass in-case-of-emergency?”

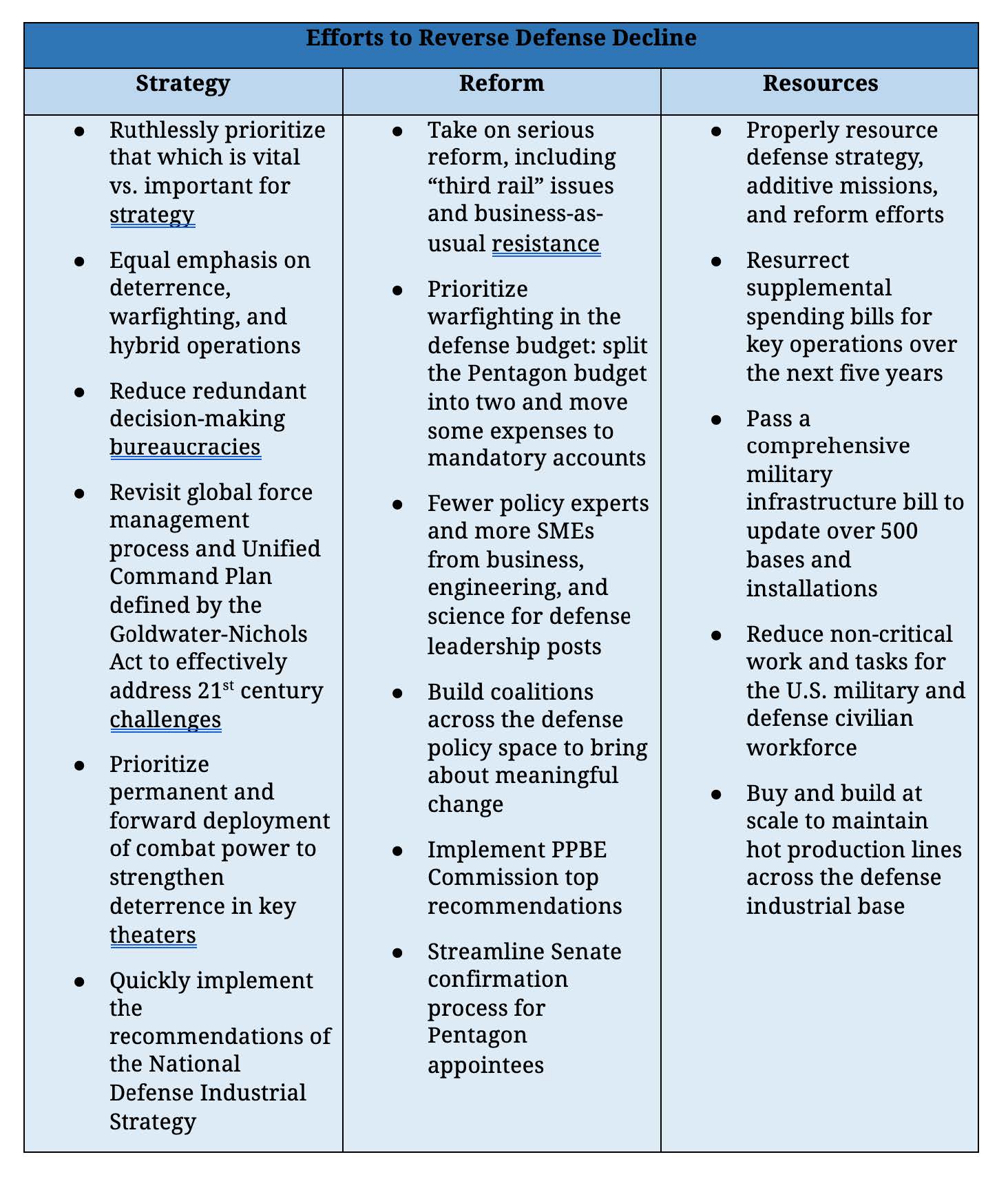

Reducing Risk in All Three at Once: Balancing Strategy, Reform, and Resources

Practical steps policymakers might consider to reverse negative trend lines for our armed forces fall into three categories: strategy, reform, and resources.

None of these efforts alone are silver bullets that will fix the defense enterprise quickly. For these to succeed, policymakers must pursue all three avenues simultaneously, as they are interlinked.

Furthermore, while reform can create a more efficient force, reform alone is not a substitute for a tuned strategy. Substantial changes to both strategy and reform beget adequate resourcing for success at scale.

Constrained Budgets Sacrifice the Future for the Immediate

Defense strategy involves making choices, which are dictated by the allocations within the defense budget. When the Pentagon’s budget is ample, it fosters an environment where policymakers can think expansively, driving strategic innovations and comprehensive reforms without the immediate pressure of financial constraints.

Conversely, a constrained budget complicates these choices, often necessitating severe modifications or the abandonment of strategic initiatives without politicians agreeing to follow suit accordingly— only widening the yawning strategy-resource mismatch.1 These forced changes can manifest as reductions in troop numbers but not mission sets; deferred modernization that harms readiness two years from now while bulging sustainment costs immediately; and halts in necessary cost-saving reforms. Budget scarcity has no track record of better ideas. It is simply a race to the bottom: a way to look and sound strategic while simply shrinking and aging the force and asking it to do more at the same time.

The net result is continuously sacrificing the future for the immediate moment of always-high readiness. It is a dangerous game of musical chairs: political appointees grab a chair and hope the music stops on the next person’s watch while adding to the deferred modernization bills that are no longer sustainable, sacrificing long-term capability for short-term solutions. While political turnover will always be a fact of life in Washington, technocratic staffing of the Pentagon political roster with business leaders, engineers, and scientists with subject matter expertise could help alleviate this strategic mismatch.

The biggest flaw with all this fiscal and policy duct-taping is that Beijing can count. Our adversaries are watching, adapting, and surpassing the United States accordingly.2 The rapidly shifting military balance in the Indo-Pacific away from America shows the result of focusing solely on the problems closest at hand.

Budget Scarcity Leaves No Room for Error or Reform

Our creaking force is the product of the budget-scarce environment of the Budget Control Act (BCA) era and sequestration. The Pentagon is still reckoning with 10 years of plans dashed,3 and budgets since have failed to dig it out of its hole. As the Pentagon’s budget tightened, choices became more difficult, but no administration admitted their strategy should be modified or abandoned. Even before war in the Middle East and counterterrorism operations in the Red Sea, the allocation of dollars underneath the topline shifted little in the past decade.4

Part of this is because there just are not that many politically acceptable cuts to make beyond (ironically) weapons systems. Pay raises are sacrosanct; no administration of either party has ever reduced defense civilians in the past 20 years;5 and science and technology programs inside R&D accounts are mostly fenced off by the Office of the Secretary of Defense and Congress.

Very little of the overall Pentagon budget is malleable. Therefore, the liquid accounts—like munitions—become the bill payers over and over. Readiness and capacity today are traded for the size and strength of the future force. But that never fully arrives, thereby setting the armed forces into their own version of a doom loop. Deferring modernization results in a shrinking, less capable, and mostly more expensive force.6 The more equipment ages, the more expensive it becomes, as assembly lines close, parts break, and replacements are needed.7

Under budgetary scarcity, replacements are often fewer in number than what they are supplanting. Capacity is a key element of a comprehensive and credible deterrent.8 No matter how advanced a next-generation platform may be or how many domains in which it can operate in conflict, wars are still largely won and lost by how many munitions, weapons, and personnel each side can muster.

Reform, therefore, is only half the battle. While reform efforts can fine-tune the military bureaucracy and create a more efficient force, increased resourcing is still required to build a force with the right size and strength to deter China and other adversaries. To do so, the U.S. military requires the capacity to absorb attrition early in a conflict and repeatedly rearm and resupply to remain in the fight. We need capacity to fight a protracted conflict and deny adversary forces the ability to win by simply outlasting us.

Policymakers should consider splitting the defense budget in two— separating warfighting operations from capital expenses—to better delineate how America’s defense posture is resourced.9 Additionally, supplemental legislation is required for the next five years to resource key initiatives outside of garrison existence and reverse the bite of the BCA. A good place to start would be investing in military infrastructure, revitalizing the defense industrial base, and rehabilitating power projection bases.10

Resources will always be constrained to some degree. Yet inflexible limits of below-inflation budget growth with unchanging strategy creates harder, worse choices. Cutting weapons quantity now eliminates economies of scale later, which contributes to exquisite buys, which then turn out to be not worth it for a too-small fleet (e.g., the B-2 bomber).11

The Reform Paradox: The Pentagon Must Spend to Save

Perhaps counterintuitively, budgetary excess is conducive to cost-saving reform. Change is never free: reform often has a price tag up front—in procuring new software systems, training staff, or initiating commissions with bipartisan buy-in. Under scarcity, the Pentagon and Congress do not have strong incentives to reform how the DoD operates and manages its resources.

This upfront price tag makes serious reform too costly—literally and politically—when budgets are tight, as adding new bills is counterproductive when cuts are being made. Forward-thinking change requires sustained commitment from stakeholders to see through and ensure outcomes, exacerbating the budgetary squeeze for the modernization bill payers for future years. The last base closure round in 2005 came with an upfront price tag of $21 billion (and later) $35 billion—a whopping invoice.12 The result today, however, is that the Pentagon is saving $12 billion per year.13 To ensure success, coalitions spanning political parties, branches of government, and outside advocacy groups must be nurtured to create the political will to see reform through to fruition.14

The Changing Military Balance in the Indo-Pacific

Small, seemingly one-off choices to live within constraints eventually create a new normal, and deterrence frays slowly over time—then suddenly. The military balance keeping peace across three theaters is no longer possible with the smaller, older force on hand.

This decline is manifesting itself in tangible consequences. The Navy is consistently expending more munitions than in can replenish in a single regional conflict, setting the stage for significant munition shortages in a potential great power conflict.15 The Marine Corps, with its shrunken fleet of amphibious warships, can no longer serve as the crisis response force it once was and is unable to meet the needs of combatant commanders and allies.16 The Air Force no longer provides air superiority—resulting recently in the first U.S. soldiers being killed by an air threat since the end of the Korean War.17

The U.S. Army active-duty force has seen a staggering decline. Though just a few years ago the Trump administration sought to build the Army up to around 550,000 troops, it saw little progress amid recruiting challenges and lack of budgetary growth.18 Today, the most recent budget request puts the Army’s end strength at just 442,000—100,000 short of that goal and the smallest it has been since World War II.19

Nowhere is this more apparent than the Indo-Pacific, where the military balance of power is rapidly shifting away from the United States. While the U.S. military remains the most powerful fighting force in the world, its strength is divided across multiple theaters. China’s rapid military buildup has tipped the scales in its favor, and now fields the world’s largest army, navy, air force, and sub-strategic rocket force alongside numerous paramilitary organizations.20 Despite a “pivot to Asia”21 and a “return to great power competition,”22 little in terms of combat power has shifted to the region,23 while Beijing continues to invest more into present and capable combat power in its own neighborhood.

Efforts to shore up the U.S. presence in the Western Pacific have seen forward-stationed forces change little over the years.24 Most concrete measures to bolster U.S. presence in the region have taken place recently and have largely failed to build combat-credible power, especially when compared to the buildup of the People’s Liberation Army.25

While China increases its military presence and more frequently deploys forces throughout the Indo-Pacific, the United States has fallen short of its goal of increased permanent presence necessary for deterrence.26 In some cases, presence has decreased, such as the Air Force permanently retiring air wings on Okinawa that have yet to find a permanent replacement.27 While the Navy has tried to supplement forces in the region through rotational deployments, temporary forces are not as effective as permanent presence.28 Unyielding global requirements have resulted in a preference for temporary deployments over permanent presence, as the geographic combatant commands battle with themselves for assets. Policymakers should consider reforming the Pentagon decision-making bureaucracy, doing away with geographically based commands, and working to instead match resources to growing strategic threats, like China.29

The failure to shift combat power to the Indo-Pacific has caused the military balance in the region to tilt away from America, leaving Admiral John Aquilino, former commander of U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, to remark that the nation has not “faced a threat like this since World War II.”30 China has the luxury of focusing its military power in the Indo- Pacific. Whereas in the event of war, only a fraction of U.S. combat power will be able to respond, with the bulk of forces having to confront the tyranny of distance.31

China’s military has not had to reckon with the same “hard choices” that have limited ours over the past three decades. China’s military spending has increased consistently, at an average of nine percent per annum. Meanwhile, the Pentagon’s budget has increased by an average of 0.8 percent annually over the past decade, well under inflation.32 This consistent investment has fueled China’s growing defense industrial base, while erratic additions and cuts across the U.S. and allies have led to inadequate industrial capacity.33 New research indicates that Beijing could be spending north of $700 billion on its military—triple its publicly reported topline and nearly equal to America’s defense budget.34 As a global power, the United States must balance competing priorities in the Indo-Pacific and elsewhere, which spreads Washington’s budget thinly across multiple theaters. Meanwhile, each yuan China invests in its military directly builds its regional combat power in Asia.

Seriousness and Urgency Required

The interplay between budgetary constraints and strategic military choices underscores a broader truth: the allocation of resources within the Pentagon is not merely a matter of fiscal policy but a determinant of military strength. Over the past decade, the United States has faced a series of “hard choices,” constrained by budget caps and the necessity to prioritize short-term readiness over long-term modernization. This has resulted in a military posture that is increasingly stretched too thin, and rising chaos is the result.

To truly address these challenges, the Pentagon must receive sustained budgetary increases. Such an investment is not merely a matter of expanding financial resources, but a strategic imperative to enact meaningful reforms. By securing a reliable increase in funds, the U.S. military can simultaneously invest in long-term modernization projects, invest in future capabilities, and pursue cost-saving reform, rather than picking and choosing from an array of least-worst options. This proactive approach will not only curb the current defense decline but will also yield substantial savings in the long run.

Mackenzie Eaglen, “Keeping Up with the Pacing Threat: Unveiling the True Size of Beijing’s Military Spending,” American Enterprise Institute, April 29, 2024,

https://www.aei.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Keeping-Up-with-the-Pacing-Threat-Unveiling-the-True-Size-of-Beijings-Military-Spending.pdf?x85095;

Mackenzie Eaglen, “10 Ways the United States Is Falling Behind China in National Security,” American Enterprise Institute, August 9, 2023.Mackenzie Eaglen, “The Paradox of Scarcity in a Defense Budget of Largesse,” American Enterprise Institute, July 18, 2022, https://www.aei.org/wp-content/

uploads/2022/07/The-Paradox-of-Scarcity-in-a-Defense-Budget-of-Largesse.pdf?x85095.Eric Edelman, et al., “Providing for the Common Defense: The Assessment and Recommendations of the National Defense Strategy Commission,” November 13

2018, p. 6. https://www.usip.org/sites/default/files/2018-11/providing-for-the-common-defense.pdf.Mackenzie Eaglen and Hallie Coyne, “The 2020s Tri-Service Modernization Crunch,” American Enterprise Institute, March 2021, p. 24. https://www.aei.org/

wp-content/uploads/2021/03/The-2020s-Tri-Service-Modernization-Crunch-1.pdf?x85095.“National Budget Estimates for FY 2025, Table 5-21: Military and Civilian Pay Increases Since 1945,” Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller),

April 2024, https://comptroller.defense.gov/Portals/45/Documents/defbudget/FY2025/fy25_Green_Book.pdf.Ibid, p. 8.

Stephen Losey, “US Air Force warns of aging fighters, poor purchasing efforts,” Defense News, September 12, 2022. https://www.defensenews.com/air/2022/09/12/

us-air-force-warns-of-aging-fighters-poor-purchasing-efforts/.Mackenzie Eaglen, “The Bias For Capability Over Capacity Has Created A Brittle Force,” War On The Rocks, November 17, 2022. https://warontherocks.

com/2022/11/the-bias-for-capability-over-capacity-has-created-a-brittle-force/.Mackenzie Eaglen, “For better defense spending, split the Pentagon’s budget into two,” The Hill, February 15, 2023. https://thehill.com/opinion/national-security/

3859140-for-better-defense-spending-split-the-pentagons-budget-into-two/.“Installation Management: DOD Needs Better Data, Stronger Oversight, and Increased Transparency to Address Significant Infrastructure and Environmental

Challenges” (U.S. Government Accountability Office, April 19, 2023), https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-23-106725.Note: B-2 Spirit stealth bombers faced a similar procurement shortchange in the early 2000s, with their quantities cut from 132 to 20 due to high unit cost

creating a budgetary squeeze. However, in hindsight, former Secretary of Defense Robert Gates has emphasized that this calculation was backwards: the higher

unit cost was a result of cutting the program, which caused costs to swell since R&D costs were amortized across a force just one-sixth of what it was initially

planned. John A. Tirpak, “Schwartz, in Memoir, Says F-22 was Traded for B-21 Bomber,” Air & Space Forces Magazine, 26 April 2018. https://www.airandspaceforces.

com/Schwartz-in-Memoir-Says-F-22-was-Traded-for-B-21-Bomber/.“Military Bases: Opportunities Exist to Improve Future Base Realignment and Closure Rounds,” United States Government Accountability Office, March 2013,

https://www.gao.gov/assets/d13149.pdf.Thomas Spoehr and Wilson Beaver, “Defense Dollars Saved Through Reforms Can Boost the Military’s Lethality and Capacity,” The Heritage Foundation, May

26, 2023. https://www.heritage.org/sites/default/files/2023-05/BG3770_0.pdf.Mackenzie Eaglen and Thomas Spoehr, “Congress: Find the Savings, Hold the Defense Budget Cuts,” 19FortyFive, March 27, 2023. https://www.19fortyfive.

com/2023/03/congress-find-the-savings-hold-the-defense-budget-cuts/.Mackenzie Eaglen, “Why is the U.S. Navy Running Out of Tomahawk Cruise Missiles?” The National Interest, February 12, 2024, https://nationalinterest.org/

blog/buzz/why-us-navy-running-out-tomahawk-cruise-missiles-209317; Mackenzie Eaglen, “The U.S. Navy’s Missile Production Problem Looks Dire,” The National

Interest, July 8, 2024, https://nationalinterest.org/blog/buzz/us-navys-missile-production-problem-looks-dire-211772.Mackenzie Eaglen, “Give Marines the Sea-Going Tools They Need to Pack a Punch,” Defense & Aerospace Report, February 5, 2024, https://www.aei.org/op-eds/

give-marines-the-sea-going-tools-they-need-to-pack-a-punch/.C. Todd Lopez, “3 U.S. Service Members Killed, Others Injured in Jordan Following Drone Attack,” U.S. Department of Defense, January 29, 2024, https://www.

defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/3659809/3-us-service-members-killed-others-injured-in-jordan-following-drone-attack/.Michelle Tan, “Chief: ‘The Army needs to get bigger’,” Army Times, October 8, 2017, https://www.armytimes.com/news/your-army/2017/10/09/chief-the-armyneeds-

to-get-bigger/.“National Defense Budget Estimates for FY 2025,” Office of the Undersecretary of Defense (Comptroller), April 2024, https://comptroller.defense.gov/Portals/

45/Documents/defbudget/FY2025/fy25_Green_Book.pdf.Rush Doshi, “The Long Game: China’s the Long Game: China’s Grand Strategy to Displace American Order” (Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press,

2021); Mackenzie Eaglen, “10 Ways the United States Is Falling behind China in National Security” (American Enterprise Institute, August 2023), https://www.aei.

org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/10-Ways-the-US-Is-%20Falling-Behind-China-in-National-Security.pdf?x85095,; “Military and Security Developments Involving the

People’s Republic of China 2023” (U.S. Department of Defense, 2023), https://media.defense.gov/2023/Oct/19/2003323409/-1/-1/1/2023-MILITARY-AND-SECURITY-DEVELOPMENTS-

INVOLVING-THE-PEOPLES-REPUBLICOF-%20CHINA.PDF.Barack Obama, “Remarks by President Obama to the Australian Parliament,” Speech, Whitehouse.gov (Whitehouse, November 17, 2011), https://obamawhitehouse.

archives.gov/the-press-office/2011/11/17/remarks-president-obama-australian-parliament.“National Security Strategy of the United States of America” (The White House, December 2017), https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/wp-content/uploads/%

202017/12/NSS-Final-12-18-2017-0905.pdf.Carl Rehberg and Josh Chang, “Moving Pieces: Near-Term Changes to Pacific Air Posture,” Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, 2022, p. 24. https://

csbaonline.org/uploads/documents/CSBA8332_(Moving_Pieces_Report)Final-web.pdf.Hans Kristensen, “(The Other) Red Storm Rising: INDO-PACOM China Military Projection,” Federation of American Scientists, September 15, 2020. https://fas.

org/publication/pacom-china-military-projection/; Mallory Shelbourne, “U.S. Indo-Pacific Command Wants $4.68B for New Pacific Deterrence Initiative,” USNI

News, March 2, 2021. https://news.usni.org/2021/03/02/u-s-indo-pacific-command-wants-4-68b-for-new-pacific-deterrence-initiative.Hal Brands, “America’s Pivot to Asia Is Finally Happening,” Bloomberg Opinion, February , 2023. https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2023-02-07/chinas-

balloon-is-least-important-part-of-us-rivalry; Aaron-Matthew Lariosa, “Marines in Japan Lead U.S. Military Changes in the Indo-Pacific,” USNI News, January

8, 2024, https://news.usni.org/2024/01/08/marines-in-japan-lead-u-s-military-changes-in-the-indo-pacific; U.S. Department of Defense, “Philippines, U.S. Announce

Locations of Four New EDCA Sites,” U.S. Department of Defense, April 3, 2023, https://www.defense.gov/News/Releases/Release/Article/3349257/philippines-usannounce-

locations-of-four-new-edca-sites/; “Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2023,” U.S. Department of Defense,

2023, p. 70. https://media.defense.gov/2023/Oct/19/2003323409/-1/-1/1/2023-MILITARY-AND-SECURITY-DEVELOPMENTS-INVOLVING-THE-PEOPLES-REPUBLIC-OFCHINA.

PDF.Mackenzie Eaglen and Dustin Walker, “American Deterrence Unpacked,” Henry A. Kissinger Center for Global Affairs, November 2023, https://sais.jhu.edu/

kissinger/programs-and-projects/kissinger-center-papers/american-deterrence-unpacked.Kadena Air Base, “Advanced fighters to temporarily deploy to Kadena through phased F-15 withdrawal,” U.S. Air Force, October 28, 2022, https://www.kadena.

af.mil/News/Article/3204073/advanced-fighters-to-temporarily-deploy-to-kadena-through-phased-f-15-withdrawal/; Unshin Lee Harpley, “Kadena Adds More

Stealth Fighters Amid ‘Increasingly Challenging Strategic Environment,” Air & Space Forces Magazine, May 1, 2024.Mackenzie Eaglen, Eric Sayers and Dustin Walker, “Congress Must Act to Boost Combat-Credible Airpower in Indo-Pacific,” Defense News, 2 November 2022.

https://www.defensenews.com/opinion/commentary/2022/11/02/congress-must-act-to-boost-combat-credible-airpower-in-indo-pacific/.Margauex Hoar, Jeremy Sepinksky, and Peter M. Smartz, “A Better Approach to Organizing Combatant Commands,” War on the Rocks, August 27, 2021, https://

warontherocks.com/2021/08/a-better-approach-to-organizing-combatant-commands/.“Open/Closed: To Receive Testimony on the Posture of the United States Indo-Pacific Command and United State Forces Korea in Review of the Defense Authorization

Request for Fiscal Year 2025 and the Future Years Defense Program,” United States Senate Committee on Armed Services, March 21, 2024, https://www.

armed-services.senate.gov/hearings/to-receive-testimony-on-the-posture-of-united-states-indo-pacific-command-and-united-states-forces-korea-in-review-of-thedefense-

authorization-request-for-fiscal-year-2025-and-the-future-years-defense-program.Lt. Col. Grant Georgulis, “Winning in the Indo-Pacific Despite the Tyranny of Distance: The Necessity of an Entangled Diarchy of Air and Sea Power,” Air

University, August 1, 2022, https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/JIPA/Display/Article/3111131/winning-in-the-indo-pacific-despite-the-tyranny-of-distance-the-necessity-

of-an/; Ulrich Jochheim and Rita Barbosa lobo, “Geopolitics in the Indo-Pacific: Major players’ strategic perspectives,” European Parliamentary Research

Service, July 2023, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2023/751398/EPRS_BRI(2023)751398_EN.pdf.Mackenzie Eaglen, “China’s Defense Budget Has Only One Trajectory: Up,” 19FortyFive, March 28, 2024, https://www.19fortyfive.com/2024/03/chinas-defense-

budget-has-only-one-trajectory-up.Seth G. Jones and Alexander Palmer, “China Outpacing U.S. Defense Industrial Base,” Center of Strategic & International Studies, March 6, 2024, https://www.

csis.org/analysis/china-outpacing-us-defense-industrial-base.Mackenzie Eaglen, “Keeping Up with the Pacing Threat: Unveiling the True Size of Beijing’s Military Spending,” American Enterprise Institute, April 29, 2024.

https://www.aei.org/research-products/report/keeping-up-with-the-pacing-threat-unveiling-the-true-size-of-beijings-military-spending/.

Join Our Newsletter

Never miss an update.

Get the latest news, events, publications, and more from the Reagan Institute delivered right to your inbox.